From Thai Villa to Tipton Sheds: How a £4M Xanax Operation Got Burned

A dark web pill press network making millions in crypto was brought down after basic OPSEC failures and a corporate tip-off. The bust highlights the gap between decentralised ambition and sloppy execution.

Between 2018 and 2019, a distributed drug manufacturing and distribution network operated across the West Midlands, coordinated remotely from a villa in Thailand. The product? Counterfeit Xanax (Alprazolam) tablets. The scale? Industrial. And the mistake?

Prosecutors described his phone as “a goldmine of information.” That means unencrypted messages, stored logs, digital trails, or worse,Classic OPSEC failure.

Brian Pitts, 30, ran point on the operation while living overseas. Alongside his partner Katie Harlow, he coordinated logistics, procurement, production, and distribution largely online. Using the darknet and crypto rails, the group produced and shipped millions of tablets throughout the UK and into the U.S.

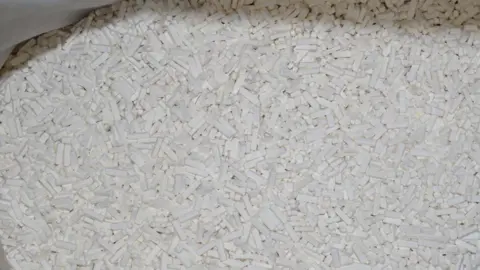

The infrastructure was straightforward. They legally acquired four pill-pressing machines capable of pressing 16,000 tablets per hour and set up shop in garages and sheds in Tipton, Wednesbury, and Wolverhampton. Using custom Xanax stamps and imported powders, they ran the equivalent of a decentralized lab network.

On paper, this wasn’t amateur hour. They weren’t cutting street corners. This was a scaled operation with clearly defined roles: suppliers, press operators, distributors, crypto handlers. It could’ve pulled in over £11 million. But they only made £4 million before it collapsed.

So what went wrong?

OPSEC Mistakes That Got Them Caught:

- Returning to the UK: Pitts was operating from Thailand with relative safety. Flying back into the jurisdiction that was already investigating the operation was a catastrophic misstep. He walked right into a trap.

- Insecure Devices: Prosecutors described his phone as “a goldmine of information.” That means unencrypted messages, stored logs, digital trails, or worse, photos and notes. Basic digital hygiene was absent.

- Using Partners’ Names: Pitts allegedly acted in Harlow’s name for parts of the op, but courts ruled she knew what was happening. Either way, linking real identities to operational logistics is a beginner-level mistake.

- Supply Chain Visibility: Pfizer’s security team caught wind of the counterfeits and triggered the investigation. That suggests traceable packaging, supply line leakage, or volume tipping off wholesale alerts.

- Local Production: Producing at home in physical locations (sheds and garages) introduces too many variables neighbors, heat signatures, physical evidence, noise. Distribution hubs and dead-drop logistics would’ve been cleaner.

Once Pfizer flagged the anomaly, the Regional Organised Crime Unit moved in. The rest unfolded predictably: coordinated raids, seizures, digital forensics, and plea deals. Four are already sentenced. Five more await.

Sentences included:

- Pitts: 8 years

- Harlow: 2 years and 1 month for money laundering

- Lee Lloyd: 7 years 2 months

- Kyle Smith: 4 years

- Mark Bayley: 6 years 5 months

The whole case serves as a real-world postmortem of a decentralised drug market failing due to weak operational security. It wasn’t morality that undid them it was sloppiness.

The mainstream headlines will lean on fear. But the real takeaway is this: if you’re going to run a decentralised logistics operation at scale, you'd better have hardened your people, tech, and tradecraft. Otherwise, you're just a loose end waiting to be tugged.

Dark Web Operational Security 101

Legal status of Alprazolam in the UK